There are so many different exercises, stretches, and techniques out there that it can be overwhelming. It seems like they just go in and out of fashion. You end up asking your patient to perform reps of some exercise just for the sake of it.

I spent years hopping from one CPD course to another, spending thousands looking for that ‘magic’ exercise that solved all of my problems. Well, that never turned up but I did learn a few valuable lessons.

In this article, I’ll explain one stretch in particular. We’ll cover what the sleeper stretch is, its flaws and why there may be a better alternative when it comes to internal rotation of the glenohumeral joint.

In this content you’ll find out…

- What the sleeper stretch is.

- What the research tells us about the sleeper stretch.

- How to assess internal rotation.

- The effect of ribcage mobility on the glenohumeral joint.

- The influence of the diaphragm.

- How your patient’s accessory muscles could be involved.

- What this all means for the sleeper stretch.

What Is The Sleeper Stretch?

I can’t say I really use the sleeper stretch, for reasons I’ll get into very soon, but there was a time when the sleeper stretch was everywhere and it still is widely used.

So firstly, what is the sleeper stretch and why is it used?

The sleeper stretch or posterior capsule stretch is used to relieve symptoms of shoulder tightness, shoulder impingement, posterior capsule tightness, and general shoulder pain.

A therapist will usually turn to the sleeper stretch to target rotator cuff and shoulder muscles when their patient has a loss of range of motion in internal rotation of the shoulder.

Throughout my years in professional sport I have seen hundreds of athletes with shoulder issues. It’s just a fact of life in contact and ball sports, which explains why the sleeper stretch is so common with therapists dealing with an overhead throwing athlete such as a cricketer or, more frequently in the United States, baseball players.

There are plenty of resources out there to tell you the exact technique to perform the stretch so, for me, there seems no reason to cover that…

What we are really interested in is what the research tells us.

What Can The Research Tell Us About The Sleeper Stretch?

For a while, there was very little research or studies around the sleeper stretch but the work you do come across now seems to be centred around athletes and baseball players.

In a 2008 study by Laudner et al, data was collected on just how effective the sleeper stretch is. Their results found that, on athletes with rotation deficit, the ‘sleeper stretch resulted in significant increases in internal shoulder rotation and posterior shoulder ROM in the dominant arm of baseball players, but it may have produced insignificant clinical changes.’

They went on to say that the sleeper stretch may limit shoulder stiffness but the ‘results cannot confirm that the sleeper stretch produces large, acute increases in shoulder ROM.’

What Does The Research Mean For Us?

The stretch may help but if it produces ‘insignificant clinical changes’ you have to ask yourself…. What other options do you have to improve shoulder range of motion?

Please don’t mistake this as me telling you to never perform the sleeper stretch. If you find it works for you then go ahead but in the mentorship, we are in the business of finding and treating the true cause.

There is one fundamental question we need to answer, why is there a loss of internal rotation at all and what can you do?

Assessing Internal Rotation Range of Motion

Before we go into just how you can improve your patient’s condition, if you’re going to try and make a real difference to the posterior shoulder then you’ll need to be able to test internal rotation.

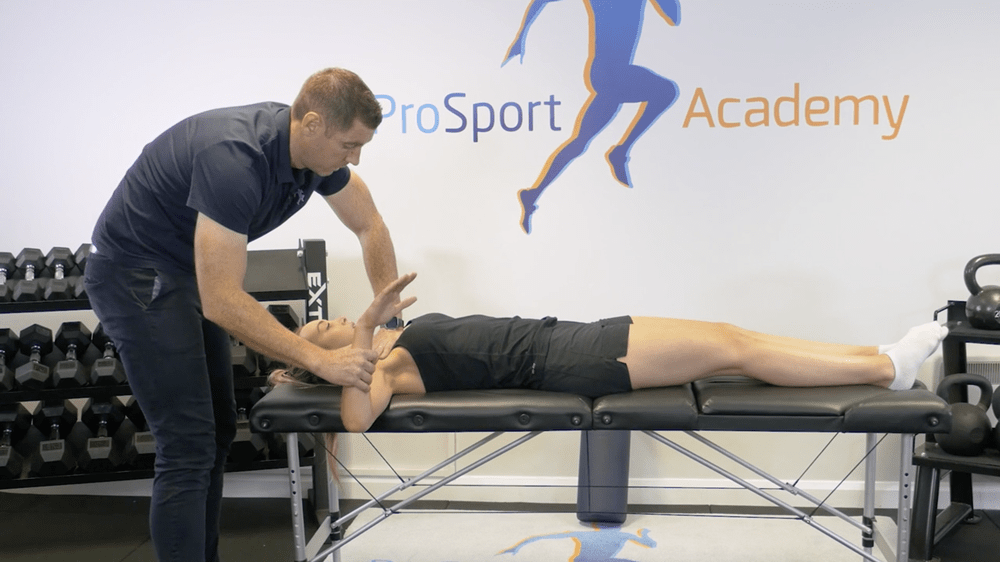

For this, you can use a standard HGIR test. It is nothing magical, just have your patient lay on their back in a flat position, put your hand on the humeral head, bring their arm out, bend the elbow at 90 degrees and bring the arm down. You’re looking for it to rest at around 90 degrees parallel with the floor.

Simple right? Well, this test is even more useful than you would think. Once you have tested, it then becomes an incredibly powerful key performance indicator (KPI) you can come back to after treatment.

It’s all well and good knowing how to check rotation of the shoulder joint but what happens if it is limited? If you’re not using the sleeper stretch what can you do?

The Relationship Between Ribcage Mobility And Shoulder Internal Rotation

Before we move on I’d like to give credit and thanks to the Postural Restoration Institute (PRI). I don’t teach using a PRI approach but I have done many of their course and they have really informed the way I work. I have fed some of their ideas and information into my own step-by-step system that we teach throughout the mentorship.

In a 2019 study, Tachihara et al found that ribcage range of motion affects upper limb movement. They concluded that ‘physical therapy applied to the thoracic spine and the upper ribs is important in the treatment of shoulder disorders.’

So how can we use this information? Well, it should lead you to ask a set of new questions… Is there a real pathology present in the shoulder capsule or could a lack of ribcage mobility be affecting shoulder motion?

Passive Ribcage Assessment For Shoulder Rotation

So we know that ribcage mobility affects the movement of the glenohumeral joint and other parts of the body.

If you can facilitate ribcage mobility then you can set your patient up for success in real-world movements including internal and external rotation of the shoulder joint.

So if you have checked GHIR, it isn’t quite where you wanted it to be and there is no pathology or rotator cuff repair that may impact, then you may want to start to help the ribcage mobilise.

Very often one of the issues I see is how the scapula is sitting on the ribcage when the ribcage is protracted. Once you get the ribcage to depress, internally rotate and retract we can get it to sit flush with the scapula.

To do this you can put your patient’s hand along the clavicle and rest your hand on top. Have them inhale and on the exhale guide the upper ribcage into depression, internal rotation and retraction. Very often if you hold then there you can see increased glenohumeral internal rotation.

Of course, the ribcage relies on other factors to access a full range of motion….

The Diaphragm, Ribcage and Shoulder Mobility

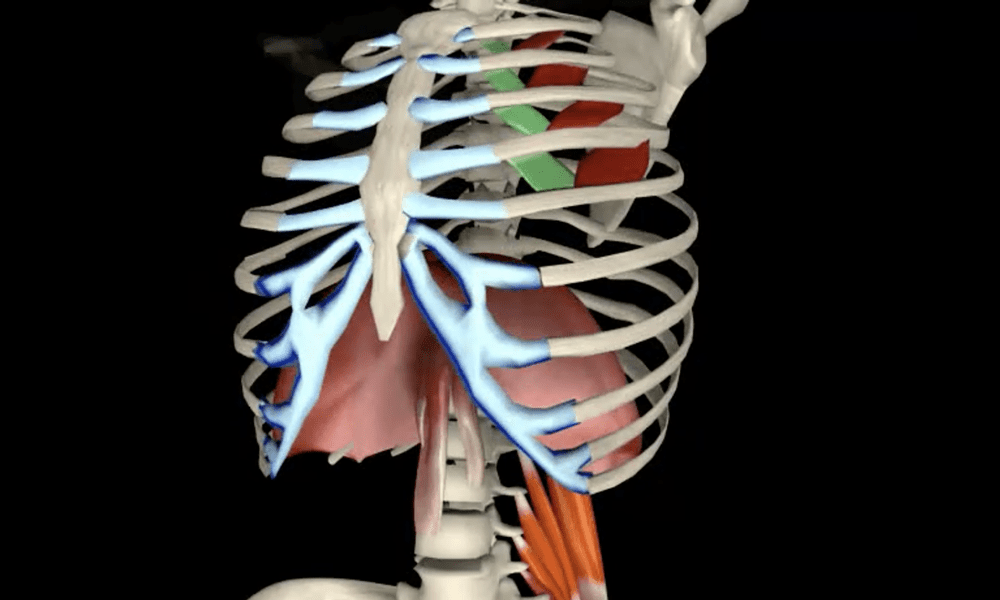

The diaphragm separates the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity, sitting underneath the lungs and exerting control over respiration.

The important thing to note here is that, amongst other attachments, the diaphragm attaches to the lumbar vertebrae and the lower ribs. This attachment means the diaphragm has a big impact on your patient’s ribcage mobility.

When you are assessing your patient you need to be conscious of what happens to their lateral ribcage as they inhale. Are their ribs flaring?

This is important because you want to create as much dome shape through the diaphragm as possible. If you can keep that dome shape when they inhale then we stimulate the crural fibres of the diaphragm that attach to the lumbar spine.

If the ribs flare and you don’t get that dome then the crural fibres are essentially being passive, the costal fibres contract and we don’t get a whole lot of time under tension of the crural fibres.

If you keep the ribcage depressed and domed whilst your patient inhales you can get load tolerance through the crural fibres and help the patient with their core stability.

Here you can coach your patient through that inhalation. Keep you hands over their lower ribs and ask them to only breathe in as much so the ribs don’t kick into your hands. This cues them to keep the ribcage retracted and down.

Very often, after those diaphragmatic breaths, they are visibly more relaxed, the space in between the clavicle and the ribs will improve, they have access to the parasympathetic nervous system and rest and digest.

After this process, you can recheck internal rotation and very often you should see an improvement.

The Affect of Accessory Muscles

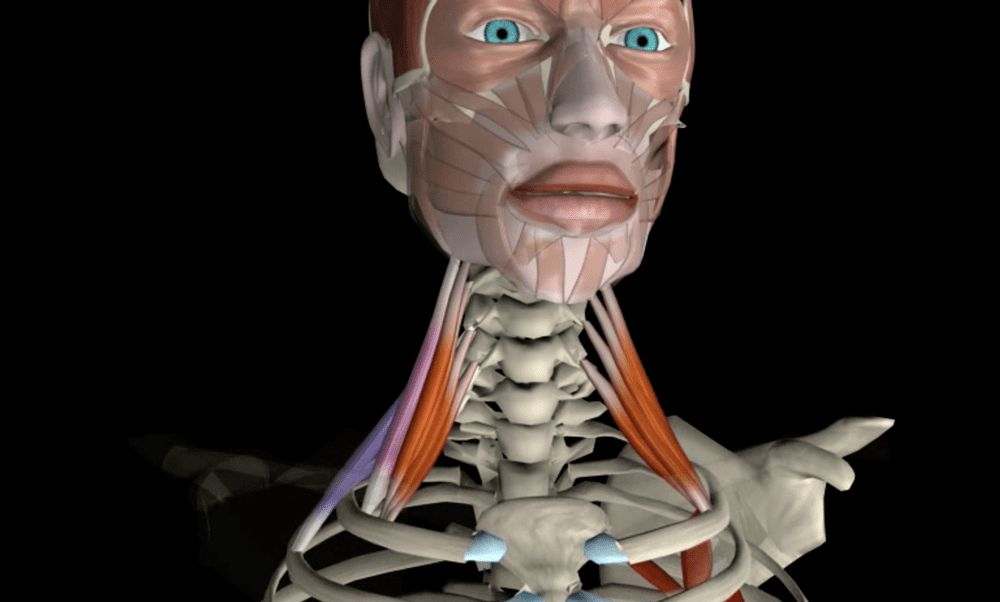

If you don’t have a good diaphragmatic breath and the crural fibres aren’t working as efficiently as they could then we tend to use our accessory muscles more.

The biggest accessory muscle that will stop the ribcage from going into internal rotation are the scalenes. The scalenes attach to the cervical vertebrae and the first two ribs. If overworked these muscles could be pulling her ribs into external rotation but for full ribcage mobility, we need both internal and external rotation.

To test whether the scalenes could be involved place your hand just under the clavicle ask your patient to exhale and guide the ribs down and in. Of there is some stiffness or sensitivity when you palpate the skin then it would indicate that the scalene is something you may want to work on.

If you wanted to prove this hypothesis you could check GHIR whilst depressing the upper ribcage, if this is the issue you should be able to change it quite quickly.

If you can desensitise the scalenes and allow the ribs to fully depress on exhalation then very often you’ll see an improvement when you check the internal rotation of the shoulders.

Is The Sleeper Stretch Really Going To Solve That Shoulder Pain?

For us, as therapists, nothing is black and white, your patient’s movement is complex but setting them up for success in the real world is your job.

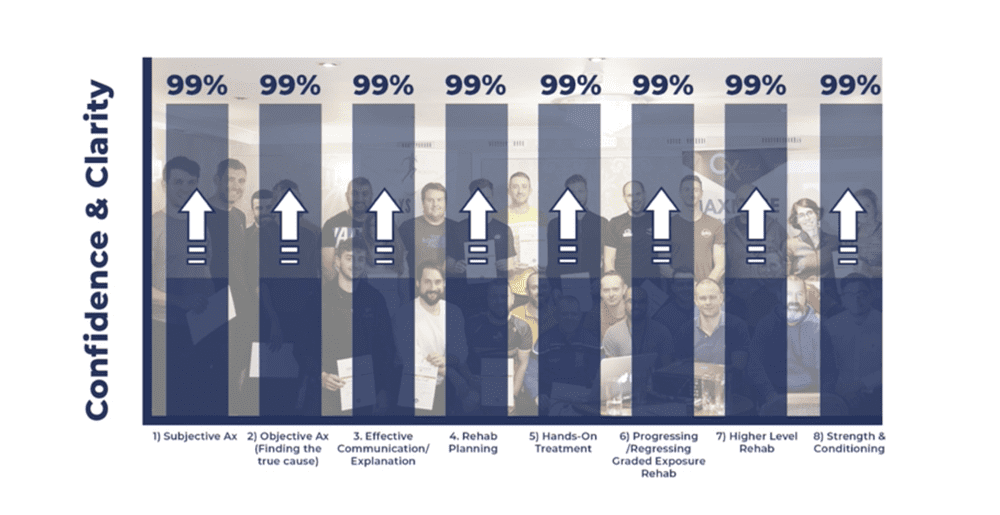

In the mentorship, we teach a structure and a step-by-step system to find and treat the true cause of a patient’s pain. We teach therapists to put the pieces of the puzzle together rather than just treating the symptoms. It’s all about understanding the WHY behind everything you do.

You cannot just perform the stretch and expect the true cause to be addressed. Perhaps sleeper stretches, exercises, hands-on, or some soft tissue work may settle some posterior shoulder tightness or symptoms but if you’re not addressing that true cause then you’re taking a risk.

You have to work smarter, not harder.

Final Thoughts on The Sleeper Stretch, Ribcage Mobility and Shoulder Internal Rotation

Rather than going through the motions and giving your patient a cross-body stretch or sleeper stretch to perform, you should always be looking at the bigger picture. Don’t put all of your hopes for bridging the gap on one technique.

If you want results, reviews, referrals, an ethical increase in revenue and a reputation as the go-to therapist then you must be looking for that true cause.

Next time you’re confronted with a stiffness of the posterior capsule or you’re about to ask a patient to perform the sleeper stretch… Take a step back, make sure all of these are playing their part and set your patient and your clinic up for success.

- Ribcage mobility.

- Diaphragm mobility.

- Accessory muscles – scalenes.